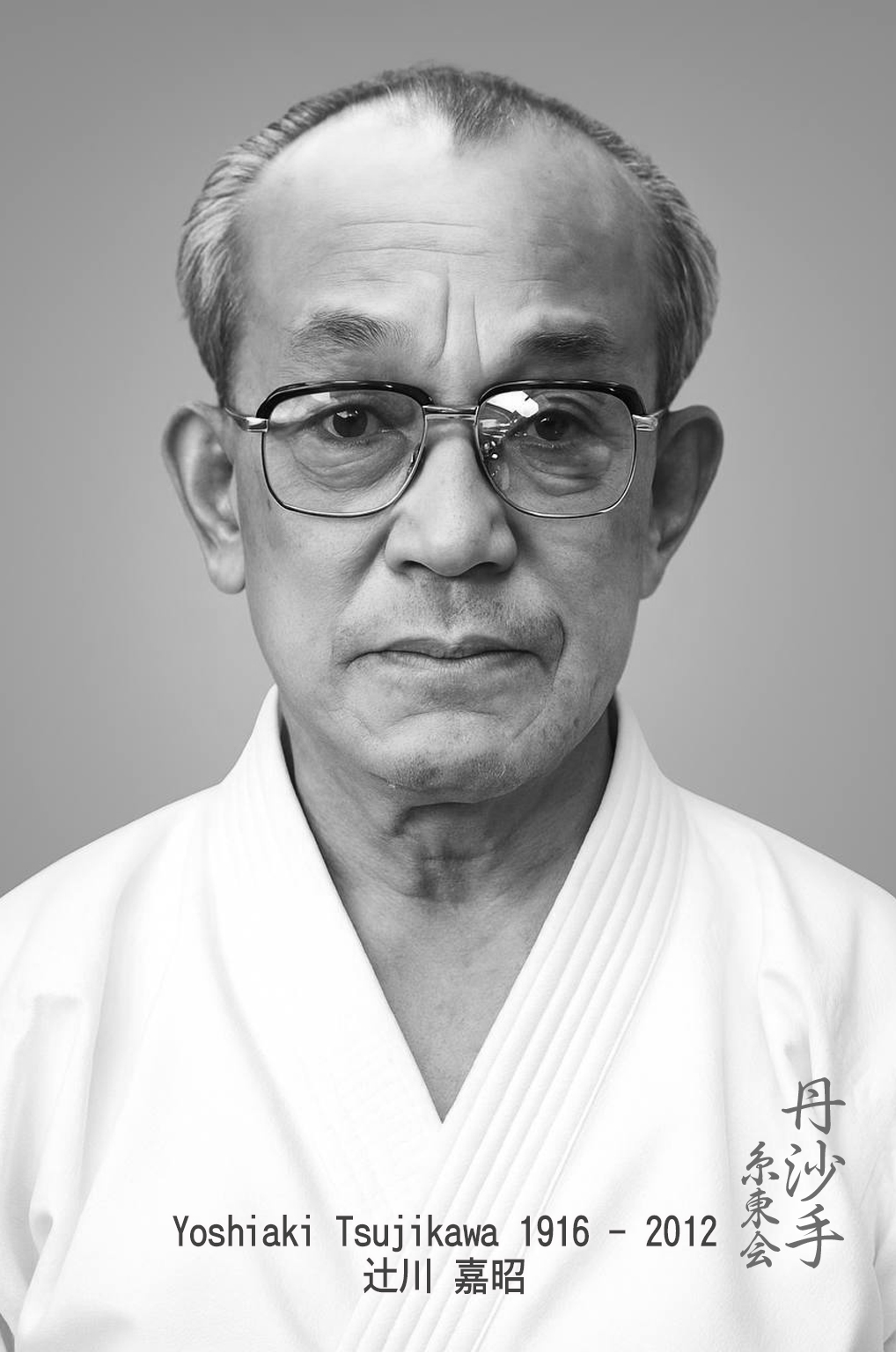

The Life and Legacy of Sensei Yoshiaki Tsujikawa

Sensei Yoshiaki Tsujikawa was born on February 10, 1916, in Kobe, Hyōgo Prefecture, Japan. From a young age, he showed an interest in martial arts and would go on to become one of the most prominent figures in postwar Karate development. In 1935, at the age of 19, he joined the Hyōgo Branch of the Dai Nippon Karatedo Kai (All Japan Karatedo Organization), led by Sensei Eiji Nishikawa, one of the most prominent students of Kenwa Mabuni. Tsujikawa would later expand his training at the organization’s headquarters in Osaka, continuing his Karate education under Founder Kenwa Mabuni himself.

In the autumn of 1938, he was appointed Deputy Head of the Hyōgo Branch when Sensei Nishikawa was conscripted into military service. Just a few years later, in July 1941, Sensei Tsujikawa opened his own dōjō, Kōbukan, at his home in Nada-ku, Kobe. That same year, the Hyōgo Branch was renamed Koa-Kai by the military authorities. Sensei Tsujikawa was appointed President of Koa-Kai, continuing his mission to preserve and teach authentic Karate during a time of great national upheaval.

In March 1944, his commitment and achievements were formally recognized when he was awarded the prestigious title of Renshi—one of the highest traditional ranks—from the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai, Japan’s historic martial arts organization. However, during the wartime air raids of 1945, both the Koa-Kai Dōjō and his personal dōjō at his home were destroyed. This tragic loss did not deter him.

By 1947, the martial arts spirit began to rekindle in Japan. In May, Koa-Kai was officially renamed Kobe Karatedo Dōshi-Kai, marking the restart of Tsujikawa’s Karate teaching activities. In September 1948, he also successfully reopened his dōjō, Kōbukan.

Soon after, in 1948, Kobe Karatedo Dōshi-Kai was divided into two separate groups. One retained the name Kōbukan, while the other became a new entity managed by Sensei Hachiro Abe. After Sensei Abe passed away in April 1949, his school was renamed to reflect his legacy as Shitoryu Karatedo Abe Style.

In 1952, Sensei Tsujikawa renamed Kōbukan once again, this time as Yoshinkan, a name it would carry forward with pride. His reputation continued to grow, and in August 1964, he was awarded the Honor of “Distinguished Person for Sports” by the Sports Association of Hyōgo Prefecture, recognizing his contributions to physical culture and martial arts.

His achievements continued to be acknowledged. On February 1, 1982, he was certified as 8th Dan by the Japan Karatedo Federation (JKF). Just a few years later, on January 15, 1985, he received the Honor of Martial Art from the Nihon Budō Kyōgi Kai (Japan Martial Art Association)—one of the highest recognitions for lifetime contributions to Japanese martial traditions.

Sensei Yoshiaki Tsujikawa passed away on April 10, 2012, leaving behind a legacy of dedication, resilience, and deep commitment to the preservation of traditional Karate. His contributions continue to influence generations of practitioners who follow the path of Shitō-ryū with the same spirit of humility and strength that defined his life.

Sensei Tsujikawa’s Recollection of Founder Kenwa Mabuni

(Excerpts from the book “Kunshi-no-Ken” – “Fists of the Man of Virtue” by Yoshiaki Tsujikawa)

As I look back on the days of training at the Headquarters Dōjō of the Dai Nippon Karatedō Kai (All Japan Karatedo Organization), around 1937 and 1938, I remember everything so vividly—as if it happened just yesterday. At the heart of the dōjō, I can still see Master Kenwa Mabuni, seated calmly with his gentle presence. Surrounding him were his students, each with their own strengths: Sensei Takamasa Tomoyori, known for his refined technique; Sensei Yoshikatsu Hase, a man of deep theory; and Sensei Miura, known for his powerful strength. Many others were also present, forming a circle around our Founder with deep respect and focus.

Training in those days was rooted in Kihon (fundamentals) and Kata. Kumite was practiced not as free sparring, but primarily through Bunkai Kumite (applied forms) and Kenkyū Kumite (study-based sparring). What we now call Jiyū Kumite (free sparring) was rare and reserved for special occasions. The training was intense—sometimes even harsh. Tsuki-geri (thrusts and kicks), Nage-waza (throwing techniques), and Gyaku-waza (reversal techniques) were part of our daily routine. Our training uniforms were makeshift—we wore quilted jackets from Kendo and underpants from Judo. The rough nature of our practice often left our gear torn. In those early years, Master Mabuni’s teaching style was also more intense and physical—quite different from the gentler demeanor he was known for in his later years.

And yet, we followed our Master as best we could.

Master Kenwa Mabuni devoted himself to the rebuilding of Japan through the path of Karate. He lived humbly and endured poverty during those postwar years, doing everything he could to spread Shitō-ryū Karatedō throughout the country. It is truly unfortunate that he passed away so suddenly on May 23, 1952, before seeing his dreams fully realized. I often imagine the sadness he must have felt, knowing that the world he envisioned had yet to come.

But I remember clearly—just as if it happened yesterday—that all of us, his students, made a solemn vow. We promised to carry on his will, to fulfill his vision, and to ensure that Shitō-ryū Karatedō would continue to grow, evolve, and inspire future generations. That vow still lives within me today.