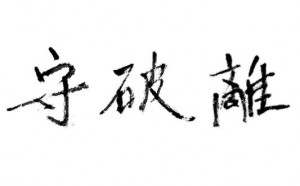

Shu Ha Ri is a term the Japanese use to describe the overall progression of martial arts training, as well as the lifelong relationship the student will enjoy with his or her instructor.

Shu can either mean “to protect” or “to obey.” The dual meaning of the term is aptly descriptive of the relationship between a martial arts student and teacher in the student’s early stages, which can be likened to the relationship of a parent and child. The student should absorb all the teacher imparts, be eager to learn and willing to accept all correction and constructive criticism. The teacher must guard the student in the sense of watching out for his or her interests and nurturing and encouraging his or her progress, much as a parent guards a child through its growing years. Shu stresses basics in an uncompromising fashion so the student has a solid foundation for future learning, and all students perform techniques in identical fashion, even though their personalities, body structure, age, and abilities all differ.

Ha is another term with an appropriate double meaning: “to break free” or “to frustrate.” Sometime after the student reaches black belt level, he or she will begin to break free in two ways. In terms of technique, the student will break free of the fundamentals and begin to apply the principles acquired from the practice of basics in new, freer, and more imaginative ways. The student’s individuality will begin to emerge in the way he or she performs techniques. At a deeper level, he or she will also break free of the rigid instruction of the teacher and begin to question and discover more through personal experience. This can be a time of frustration for the teacher, as the student’s journey of discovery leads to countless questions beginning with “Why…”. At the Ha stage, the relationship between student and teacher is similar to that of a parent and an adult child; the teacher is a master of the art and the student may now be an instructor to the others.

Ri is the stage at which the student, now a high ranking black belt, separates from the instructor, having absorbed all that he or she can learn from them. This is not to say that the student and teacher are no longer associated. Actually, quite the opposite should be true; they should now have a stronger bond than ever before, much as a grandparent does with their son or daughter who is now also a parent. Although the student is now fully independent, he treasures the wisdom and patient counsel of the teacher and there is a richness to their relationship that comes through their shared experiences. But the student is now learning and progressing more through self-discovery than by instruction and can give outlet to his or her own creative impulses. The student’s techniques will bear the imprint of his or her own personality and character. Ri, too, has a dual meaning, the second part of which is “to set free” As much as the student now seeks independence from the teacher, the instructor likewise must set the student free.

Shu Ha Ri is not a linear progression. It is more akin to concentric circles, so that there is Shu within Ha and both Shu and Ha within Ri. Thus, the fundamentals remain constant; only the application of them and the subtleties of their execution change as the student progresses and his or her own personality begins to flavour the techniques performed. Similarly, the student and teacher are always bound together by their close relationship and the knowledge, experience, culture, and tradition shared between them.

Ultimately, Shu Ha Ri should result in the student surpassing the master, both in knowledge and skill. This is the source of improvement for the art as a whole. If the student never surpasses his master, then the art will stagnate, at best. If the student never achieves the master’s ability, the art will deteriorate. But, if the student can assimilate all that the master can impart and then progress to even higher levels of advancement, the art will continually improve and flourish.

From the book “Flashing Steel – Mastering Eishin Ryu Swordsmanship” by Masayuki Shimabukuro and Leonard J. Pellman